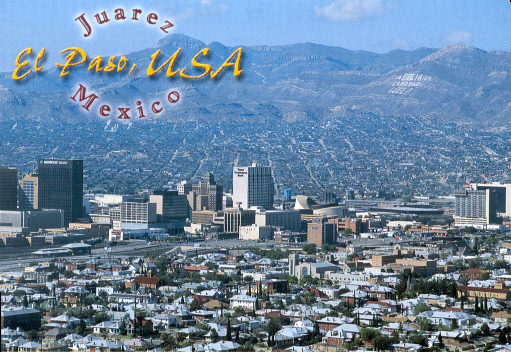

El Paso (in foreground) and Jaurez.

by Tim Janof

El Paso, for those who haven't been there, is a fascinating town because it lies right on the border between the United States and Mexico. There are several exits along Highway 10 where one can easily drive across the border into Mexico, though it is more difficult to return. When driving east along the highway, El Paso, with its paved roads and multi-story houses and office buildings is to the left, while to the right is Juarez, Mexico, with its dusty roads and small, single-story houses that huddle together on hillsides and crowd a vast valley. The contrast between the two countries is striking, and seeing it firsthand is well worth a visit.

El Paso (in foreground) and Jaurez.

Bailey invited me to El Paso and gave me unrestricted access to the entire affair, which started on Friday and ended Sunday morning. I was invited to the rehearsals, recording sessions, meals with the musicians, backstage before and after the concert, the celebratory dinner afterwards, and the goodbyes at the airport. Not only did this allow me to experience the emotional crescendo towards the concert, but it gave me insight into how a concert of this caliber is put together. I also enjoyed getting to know the musicians.

The concert was sponsored in large part by B. J. Graham, who, along with her late husband, Robert M. Graham, Sr., acquired her wealth by inventing "liquid paper," a.k.a. whiteout, the white liquid that is used to cover up typos. Back in the days before word processors, Mr. Graham had a secretary who was a terrible typist. In order to preserve his sanity, he decided that he needed to come up with a way to prevent his secretary from having to re-type entire pages whenever she made a mistake. He first tried gesso, the white liquid that is used by artists to prime a raw canvas before using oil paints, but it didn't dry quickly enough. Thus, Mr. and Mrs. Graham's innovation was to develop a liquid that covers up mistakes and dries in a decent amount of time. This small but important invention made the Grahams their fortune.

Given that Starker's performing career is now winding down, each of his concerts is an experience to be cherished. Bailey is very much aware of this and his driving mantra was, "This is historic � this is historic ... this is historic." He made sure that the entire event, including the rehearsals, was documented for posterity, though not necessarily for public release. He flew in Adam Abeshouse from New York, a Grammy Award winning audio engineer who has, among others, recorded pianist Garrick Olson and the Juilliard Quartet, and he hired a local video technician to film the concert. He also flew in fantastic musicians from New York, violinists Kurt Nikkanen and Soovin Kim and violist Kirsten Johnson. And because Starker no longer travels with his own instrument, Bailey had the 'Francesco' Gofriller flown in for Starker's use. (Interestingly, when Starker first tried the cello, he practiced double stop thirds and fifths in order to get to know it.) Bailey went to incredible lengths to make certain the concert was a success, and he spared nothing to ensure that Starker was treated like "The King of the Cello," as the advertisements for the concert said.

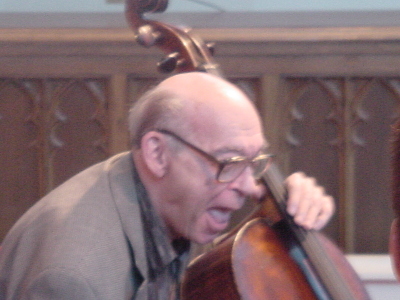

Bailey and Starker.

Bailey believes that it's entirely plausible to think of Starker as the king. (When walking through the foyer prior to the concert, I overheard one person say, "I thought Yo-Yo Ma was 'The King of the Cello.' ") When one looks at Starker's illustrious career, one can't help but be in awe of what he as accomplished. Very few can claim to have excelled in virtually every role as a musician: soloist, chamber musician, recording artist, principal cellist of world class orchestras, writer, sheet music editor, and pedagogue. If Starker isn't deserving of this title, who is?

When Bailey first approached Starker with the idea of playing in El Paso two years ago, there was a lot of discussion about what the program would be. Starker, who is almost 80 years old, was not inclined to do a full recital. Instead, he preferred to play chamber music. Since he was to be the centerpiece of the concert, it was agreed that the program would feature the cello. In fact, each piece would feature two cellos, in which he would play the first cello part:

Starker used to play an arrangement of the last movement of the Boccherini Quintet as an encore in his recitals, and the last time he played the Boccherini duet was with Zara Nelsova. This concert also had meaning for Starker because he appreciated the fact that Bailey was "carrying the flag" for musical beauty and the cello, which is what Starker asks his students to do when they graduate from his cello class.

When I first attempted to walk into the rehearsal at First Baptist Church I was stopped by Adam Abeshouse, the recording engineer, because the tape was rolling. He shared a second set of headphones so that I could listen in, and what I heard was heavenly, the Schubert C Major Quintet. Of course, Abeshouse, a typical engineer, was shaking his head with each slight imperfection of ensemble, marking in his score where things weren't quite together. Not having his Grammy Award winning ears, I found his reaction to be more amusing than a cause for concern. I knew the concert would be incredible.

Billboard for the concert on the side of Highway 10.

A few minutes later, there was a break and Abeshouse reluctantly agreed to let me go into the hall, where I was greeted warmly by both Bailey and Starker. Bailey explained to the others that I had come all the way from Seattle. Violinist Soovin Kim asked, with light-hearted disbelief, "You came all the way from Seattle?" Starker explained to the others how cellists are an unusually enthusiastic bunch, which seemed to ease the bewilderment of the non-cellists in the room.

After they finished rehearsing the Schubert it was time for lunch, and we all piled into a couple of cars, me with Starker and Bailey. We sat outside on a balcony at a restaurant with Starker to my immediate left and Bailey across from me. I must say that despite the fact that I've had similar moments with many of the better known cellists, I couldn't help thinking, "I'm having lunch with Janos Starker!"

In retrospect, the location of our meal was far from optimal. Starker talked so softly that I found myself leaning in closely in order to hear him above the street noise, and I didn't want to miss a single word. Who wouldn't want to learn about his times in the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and his memories of cellists like Frank Miller, whom he referred to as "perhaps the greatest principal cellist of all time"?

I was told on our drive to the restaurant that the other musicians were from New York. I had never heard of them, so I assumed from this description that they played in a lot of Broadway shows, substituted for players in the New York Philharmonic on occasion, and maybe played in some movie soundtrack recordings. I asked Soovin Kim at one point afterwards if he found the New York scene to be competitive. He replied, "No, not really," which I found to be a bit surprising, given how the New York music scene is well-known for its cutthroat competition. It was only after reading his bio in the concert program that I understood why he gave this unexpected reply. He had won the 1996 Paganini Competition, the 1997 Henryk Szeryng Foundation Career Award, and the 1998 Avery Fisher Career Grant. Of course he didn't find the New York scene to be competitive; he's one of the best violinists in the world! And then I read the bios of the other two. Kurt Nikkanen is an accomplished soloist who has played with some of the world's greatest orchestras, and Kirsten Johnson was only 17 years old when she first soloed with the Chicago Symphony. She's also a regular performer at highly regarded chamber music festivals such as Marlboro. Bailey truly honored Starker by bringing in this group of musicians.

The rehearsals were fascinating. I found myself vacillating between thinking of Starker as the legendary cellist that he is and him being just one of five musicians. The latter was easy to do because his sound blended so well with the group, if not on the edge of being overpowered at times. He was the grand old man of the group, being at least twice the age of everybody else, but he didn't lord over the others whatsoever. He'd make the occasional comment, perhaps share a brief anecdote, or quote from one of the late greats, but he was mostly quiet and all business.

Starker's comments during rehearsals were always brief, but very meaningful. He suggested that vibrato should be at most a light shimmer, since vibrato that is too wide can detract from pure intonation. He prefers that spiccato be brushy instead of bouncy, because notes are better heard when they are given more substance. In the slow movement of the Schubert, he encouraged the others to change the bow as much as they needed in order to sustain the musical line; "You shouldn't have an ego about trying to sustain the bow for so long. The music is what is important, not proving to yourself how long you can hold a single bow stroke." Sometimes others would take his suggestions, and sometimes they wouldn't. I asked Starker about this afterwards and he said that he didn't mind if they didn't take his advice, since they were professionals, and he wasn't giving a lesson, though Soovin Kim did mention later he would steal some of Starker's bowings in the Schubert for future performances.

When the others solicited Starker's feedback, he'd always reply with good humor. At one point Starker was asked if he felt he was being rushed in the last movement of the Boccherini Quintet, which has an incredibly demanding first cello part. He replied, "I don't know. I'm busy playing." Or when he was asked if he was ready to start the last movement of the same work, he said, "As Heifetz once said, 'I'm not ready, but I'm not getting any readier.'" Starker's sense of humor kept the atmosphere of the rehearsal light and enjoyable.

It was amusing to watch Bailey throughout the rehearsal. He'd look at me frequently, saying with his eyes, "I can't believe I'm playing with Starker!" What could be better than playing the beautiful intertwining lines of that heavenly cello duet in the first movement of the Schubert with one of the greatest cellists in history? What could be more exhilarating than playing those raucous low register unison lines for the cellos in the same work? What a thrill it must have been for Bailey.

There were times when Starker's stunning virtuosity brought the rehearsal to a halt. When Starker played a sixteen-note run with a flawless upbow staccato in the Boccherini Quintet, Bailey was so taken aback that he lost his place. Bailey signaled the others to stop, saying, "You have no idea how overwhelming it is to be a cellist playing next to this man�." So they started over and when Starker played the same passage, Bailey lost his place yet again, "Sorry, sorry." Bailey survived the third attempt, however.

An amazing phenomenon to watch was how Starker improved with each rehearsal. This was particularly impressive because he never brought the cello back to his hotel to practice. His 16-note upbow staccato in the Boccherini Quintet, for example, grew from being incredibly impressive to having a stunning sparkling clarity. If he's this good in the winter of his career, just imagine how he played when he was in his prime. Starker's technique is still unbelievable.

The night before the concert, Bailey and I went to his studio to pick up a cello for me. Having to play the E-flat Prelude in the Seattle Violoncello Society's Bach Suite marathon the following week, I didn't want to not touch a cello for three days. Starker said, "So you drew the short straw ...." when I told him I was playing this difficult movement. Bailey let me borrow a very fine instrument, made by Carl Becker in 1934. He took me to the school's auditorium, walked up on the empty stage, pulled out a chair from the back, took the cello out of its case, and said as he was tuning it, "I want to hear your Bach and I want to hear it now." Panicked, I silently ran through my vast Inner Excuse Rolodex (IER), "It's 10pm, I got up at 3am to catch the plane, I have never touched the cello before me, I'm a cellistic schmoe compared to Bailey ...." All these thoughts and many more gelled into the succinctly spoken reply, "Sure." Bailey handed me the cello and turned up the semi-blinding stage lights while keeping the house lights off, so that the experience was as close to a performance condition as possible. Still stunned, I frantically did a quick warm-up scale to sort of familiarize myself with the cello, which was an exercise in futility. And then it was showtime.

I didn't play very well. In fact, I sucked. I was tight as a drum, and there were a couple of memory slips, and some nervous right hand "vibrato." And Bailey's opening "okay" after I finished, the kind of "okay" that starts on a high pitch and ends on a low pitch, pretty much said it all, the kind that generally means, "That was awful, but I won't tell him so." He then gave me a truly inspired lesson, discussing ideas on how to play with more musical variety. He took the cello and played parts of the prelude himself with a wonderful open and ringing sound and with enviable vitality and nuance. He then had me run through the entire prelude two more times, asking me to start off stage, walk to the chair, sit down, and just start playing. Each time got better and better as I calmed down and my mind raced with ideas. We left together an hour later, me feeling exhausted, sheepish, but inspired.

The next morning, as I was listening to the rehearsal, I was trying to figure out what I might discuss with Starker in an interview with him, if the opportunity arose. Still feeling down about how I played the night before, I recalled the story of George Plimpton playing the triangle in a concert with Leonard Bernstein and the New York Philharmonic. Plimpton, a journalist, and not a musician, is well known for trying things that are not in his field of expertise for the sake of adventure and so that he could write about his experiences later. It occurred to me that I could do a "Plimpton" and ask Starker if he would give me a cello lesson. What did I have to lose? If it went poorly, it would still make a good read, perhaps a better one. Unfortunately, or perhaps fortunately, he declined my request, but he said he would be happy to talk with me over lunch. I was simultaneously disappointed that I wouldn't have a lesson, and excited to have the opportunity to interview him, which I did later that day. One exciting piece of news he shared with me during the interview is that a new book will be published about him in the fall, and it will include a CD of one of his recitals!

Backstage was a madhouse in the final hour before the concert was to begin, except for Starker, of course. While everybody else was in an extremely heightened state of alert, Starker was as cool as can be, serenely smoking a cigarette as if he didn't have a care in the world. Bailey, on the other hand, had his hands full. In addition to doing some last-minute warm-ups on his cello, he was darting around, coordinating innumerable logistical details, like making sure that the stage manager assigned someone to the back door so that Starker could be let out for a quick smoke whenever he felt like it. It was in the middle of this frenetic excitement that the audio and video engineers got into a heated argument. The audio engineer was worried that the cameramen's whispers in the hall would be picked up by the microphones, and the video engineer didn't like being told how to do his job. Bailey was called in to mediate and he did his best to re-direct everybody's energies into something more productive, simply saying to the video engineer, "Just remember that we are recording history. Please just do the best you can." And then we all left and the video control room's door was huffily slammed shut behind us.

After that drama Bailey had to do a pre-concert lecture and Starker agreed to tag along. Bailey began his talk by saying that he had grown up completely in awe of Starker and that most cellists can only claim to have done 10% of what Starker has accomplished on such a high level. Bailey pointed out to those in the audience that they were going to witness history that night. Starker, with his typical wry sense of humor, replied "It's a bit surprising when one is referred to as 'history.' "

Starker then shared an abbreviated version of his article, "That Room at the Top," in which he described the six stages of a soloist's career:

Starker felt that he was on the verge of the last stage now, which caused the crowd to go "Awwwwww." He then referred to his violinist grand-daughter, as he often did during the weekend, with whom he would be performing in the next few weeks. The audience was clearly charmed by him.

The church was packed, including the balcony, and the energy in the expectant crowd was palpable. Clearly, El Paso has a powerful thirst for classical music, which one might not expect in a remote border town in Texas. All of El Paso Pro Musica's concerts have been incredibly well attended, but this was obviously an extraordinary event, given that every seat was filled.

When the musicians first walked on stage, Bailey and the others held back while Starker continued to the front. Starker was greeted with a prolonged standing ovation, a thanks for his lifetime of service to music. This crowd was ready for a great performance.

The concert was two hours of inspired music-making. Starker was clearly lifted by the energy of the crowd and he seemed to be having a great time. His playing, though a bit on the soft side, was full of energy and virtuosity, and he moved with the music as he played. He had stepped it up yet another notch above how he played in the rehearsals, again without having practiced. How does he do it?

There was something very moving about watching Bailey and Starker play together; one couldn't help but see the passing of the torch from the older to the younger generation. Bailey had the brighter, more muscular tone of the two, and he played with long, singing, arching phrases and with a wider vibrato, whereas Starker had a more muted tone, a thinner vibrato, and he phrased using more of a spoken articulation, like a recitative. Bailey told me later that his biggest challenge was to continue to play like himself, and to resist the urge to approximate Starker's style. Bailey should definitely continue to play his own way; he is a great cellist in his own right.

When the concert was over, the audience rose to its feet in appreciation. People went up to B.J. Graham, who underwrote the concert, and thanked her profusely for making the concert possible. Graham said excitedly over and over, "Wasn't this well worth it! Wasn't this well worth it? �." The concert was a triumph in every respect.

The next morning, we picked up Starker at his hotel and drove him to the airport. I stood aside as I watched Starker stand in line for his boarding pass. It was odd to see him doing such a mundane task, and it occurred to me that Starker has stood in countless ticket lines as part of his grueling traveling schedule. What a lonely and tedious life it must have been at times. After Starker received his boarding pass from the ticket agent, who clearly had no idea who Starker was, we walked him up to the security gate, hugged him goodbye, and watched him slowly rise up the escalator to his gate. It was an honor to spend time with "The King of the Cello" and with Zuill Bailey, whose career I'm convinced will continue to grow and flourish.

5/1/04

| Direct correspondence to the appropriate ICS

Staff Webmaster: Eric Hoffman Director: John Michel Copyright © 1995- Internet Cello Society |

|---|