by Dimitry Markevitch

Ever since Jean-Louis Duport's Essai sur le Doigté du Violoncelle, written two hundred years ago, very little has been done to systematize cello fingerings. Cello technique has made great strides under the influence of personalities such as Pablo Casals, already almost a hundred years ago, and many methods have been published, from Bernhard Romberg to Diran Alexanian, but none has discussed at length the vital question of fingerings, Carl Davidov being somewhat the exception.

Cello playing has developed in a very haphazard manner. Some individual performers brought their idiosyncrasies, which are usually too personal to be used by other cellists, but on the whole one has to admit that our technique has basically not changed all that much since 1800. The definitive modern treatise on cello fingerings has yet to be written.

Luigi Silva, who had very sound ideas on technique, was working on a cello method with Rudolf Matz, but his untimely death stopped this interesting project. Victor Sazer's recent book, New Directions in Cello Playing, is a step in the right direction, even if he sometimes proposes extreme though always thought-provoking solutions. The cello equivalent of Galamian's Principles of Violin Playing and Teaching unfortunately does not exist.

As I have been playing the cello for seventy years and have experienced the impact of three centuries (Maurice Eisenberg passed on to me the precepts of Casals, who was of the last century. Then I became Piatigorsky's first pupil, who was definitely of this century. Now I teach students of the next century), I feel that this privileged situation allows me to diagnose the present state of cello playing more accurately.

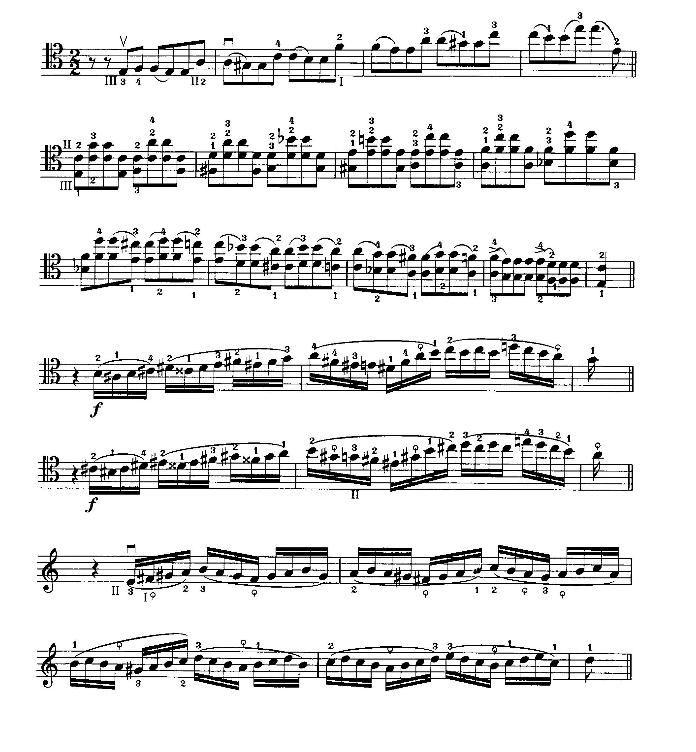

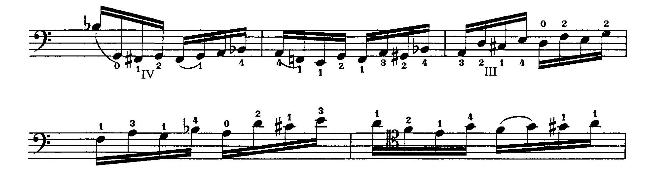

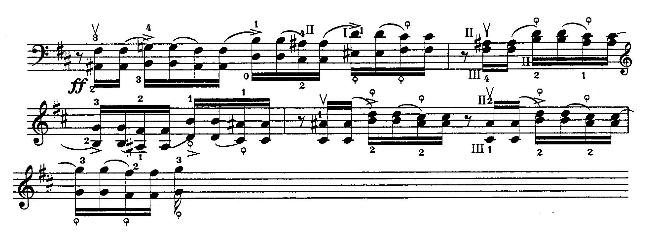

To begin, let me give some examples (taken from Saint-Saëns Concerto) of what I mean by a more rational fingering technique:

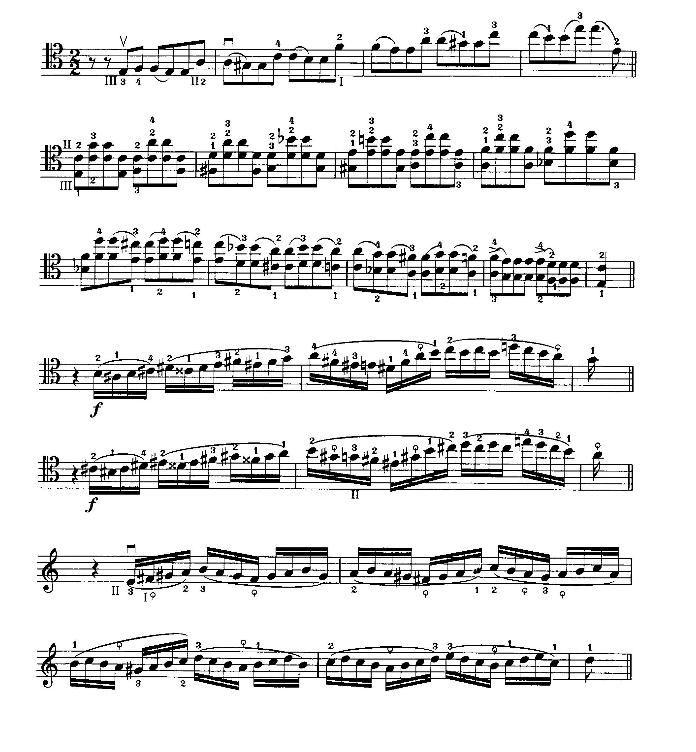

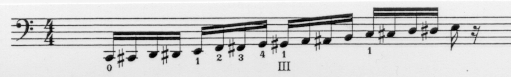

Scales are always a good laboratory in which to experiment when looking for good fingerings. Let's not forget that music is, most of the time, made up of bits of scales, so the following very useful basic fingerings, which avoid open strings, should become familiar to all cellists for the first two octaves:

The same fingerings go for all keys. The only exceptions are in the C and G scales, which begin:

Open strings should be used for definite musical purposes and not just for facility's sake, as they often stick out like sore thumbs.

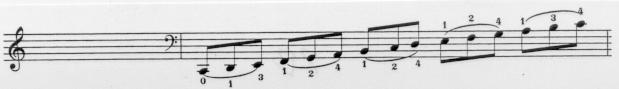

These passages in the first movement of the Haydn D Major Concerto show that, with a little imagination, one can always find new and interesting possibilities:

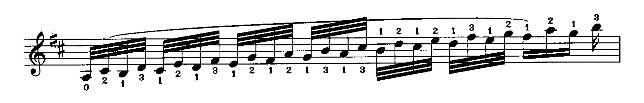

Duport established the standard fingering for the chromatic scales: 123, 123, but at the same time, Baudiot in the Paris Conservatoire Method of 1805 suggested this fingering: 12, 1234, which has been completely forgotten. To my mind, the latter fingering is much more sensible because the left hand moves less. By the way, this is the fingering that Heifetz used on the violin to great effect. Galamian also recommends it in his book.

The question of audible shifts is still problematic today. Slides and portamentos made for expressive or lyrical purposes should not be confused with left hand moves. Unfortunately, we too often hear slides in passages where they have no place, made only for convenience. If you listen carefully to most cello performances, you will realize that there are too many unnecessary slides. We are used to that kind of playing which is, sadly, the rule, not the exception.

The function of the slur is better described by the French word liaison, or connection, as it connects the notes, the opposite of staccato, which means detached.

If a player chooses, for special musical reasons, to connect two notes with a slide, they should be played,

sliding with the finger that will play the second note.

But for quick inaudible shifts, one does the contrary, sliding with the finger which just played, making an extension towards the new note. It is also always beneficial to try to make shifts coincide with changes of bow.

Broken thirds are another of these problems. The usual fingerings, with the 2-2 slides are not aestheticallly pleasing, even if we have found it normal to play them this way since Duport. I will show you with the following passage what I suggest, which is from the end of the first movement of the Haydn D Major Concerto, :

This type of fingering, which eliminates all slides, can be used in most broken thirds passages. Left arm and thumb should always lead the way.

Here is another example from the Schumann Concerto:

Some expansions (extensions), such as between 3-4, if used wisely, can help create a cleaner execution. Here are some examples:

In playing these last two examples, one should be aware of the active role of the thumb, well described by Maurice Eisenberg in his excellent book, Cello Playing of Today, p. 84.

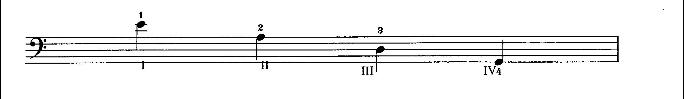

Silva, in his editions and transcriptions, uses very judiciously the fingering 1 2 3 4, which is not exploited fully by today's cellists:

Expansions combined with concentrations (contractions) can also be very useful:

Here is a good rule for playing fifths on neighboring strings. Always use the smaller numbered finger on the highest string:

Luigi Dallapiccola's Adagio from his Ciaccona, Intermezzo e Adagio, edited by Gaspar Cassado, is a good exercise for this important aspect of smooth performance.

I feel that cellists often don't pay enough attention to voicing and the use of different strings to vary the sound, especially in Bach, which brings out the inherent polyphony:

Playing on the same string, introduced on a large scale in the last century by Davidov, and used ever since by the Russian cellists, is very effective for lyrical passages in the romantic repertoire. For music of the Baroque and Classical eras, however, it can be very detrimental to good taste and style.

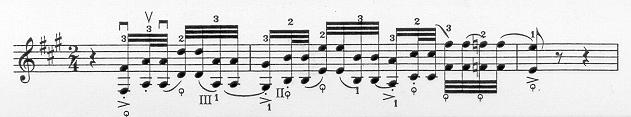

Here are some examples taken from the Bach Suites:

For those playing the familiar Hanus Wihan version of the Dvorak Concerto, and not the much more musical original version by Dvorak himself (published in Prague), I have this fingering to offer, keeping the first or second fingers on the same spot (thumb on A only).

Try to follow this general rule: Moves, change of positions and shifts, should be kept to a minimum.

Some well-known octave passages, such as those at the end of the third movement of the Haydn D Major Concerto, or at the end of the Tchaikovsky Rococo Variations, often sound as if they were played on a soapy fingerboard. They should be played with fingered octaves in the following manner:

Fingered octaves, once mastered (it's not that difficult), can be very useful in similar passages in other works as well. It avoids all unnecessary slides and help to produce a more modern type of performance, which should be the aim of present day cellists. It is usually preferable for octaves above middle D on the D string to use the fingering "thumb and 2."

In thumb position, though, the thumb itself, unless you perform double stops or octaves, should be kept only on one string, mainly the A string.

This brings me to the general question of playing double stops without anxiety. One should always keep in mind a principle already alluded to by Kato Havas in her violin books -- keep a mental emphasis on the finger which holds the lower figure. For instance, number one has precedence over three, and two over four. The thumb, in all cases, outranks them all. This means that, in thirds, the finger playing on the upper string should be concentrated on, and, in sixths, the lower string. At first it should be practiced with the bow playing only on the string on which the lower numbered finger is playing. Try it and you will be amazed at how much more easily your double stops and octaves will come out. You can start with practicing the following fingerings for this passage from Dvorak 1st Movement:

The search for rational fingerings cannot stay static. It is a neverending exploration that should fascinate every cellist. New and better fingerings exist, but it takes perseverance to find them. Ultimately, fingerings should be chosen for musical reasons, not convenience.

The ideas I have discussed demonstrate that there is still a long way to go before we establish a modern and rational technique. In addition, we have the right hand to examine, with aspects such as staccato, which is almost a lost art. All of this is absolutely captivating, but must be the subject of another article.

Before closing, I would like to mention an aspect of cello construction that is completely overlooked: string length, which is usually too long, making playing uncomfortable. For mysterious reasons, some unknown maker established the standard length between the nut and the bridge as 69 cm. This is too large, especially for someone with smaller hands. I feel that the correct length should be 68 cm. My cello is set at this measurement and it is definitely very agreeable to play.

© Dimitry Markevitch, May 5, 1999.

| Direct correspondence to the appropriate ICS

Staff Webmaster: "webmaster" Associate Webmaster: Webmaster Director: John Michel Copyright © 1995- Internet Cello Society |

|---|