Stewart

>> Ms. Walton has certainly accomplished a major amount in one lifetime! I get the feeling that she is by no means through either. As a fledgling adult cello student, it is reassuring to imagine that I may be playing well into my seventies.

Betsy

>> I had the privilege of playing with Frances Walton in an amateur orchestra section several years ago. Besides being a wonderful cellist, she's a warm and generous person. I learned more about fingering sitting next to her and watching what she did than from anyone before. It was truly a pleasure to play with Frances.

MaryK

**If you would like to respond to something you have read in 'Tutti Celli',

write to editor@cello.org and type "Membership

Letter" in subject field. (Letters may be edited.)**

by Tim Finholt |

|

TF: You had a diverse artistic experience in Berlin before you began studying the cello.

ES: Yes, I feel very fortunate. I played the violin and piano before starting my cello studies. I was also a dancer for seven years, until age 11, in the Berlin State Opera. My dance experience greatly heightened my awareness of body motion and balance, and has been of great help in diagnosing my cello students' technical problems.

I performed as a dancer in 15 different operas, which was an absolutely fabulous way to be involved with music, since I stood next to some of the world's greatest singers. The experience of listening to their wonderful voices and experiencing the operatic atmosphere was incredibly stimulating. The intense training and preparation for the performances had an enormous influence on my young being.

TF: Who did you study the cello with?

ES: I studied with Professor Karl Niedermeyer, my first cello teacher, from 11 to 14 years old. He was the star pupil of Hugo Becker and later the principal cellist of the Staatstheater in Berlin. He was known as a marvelous cellist who had a gorgeous tone and a fabulous technical command. I particularly remember his beautiful, fluent bow technique. He advanced me so quickly that by age 14 I entered the prestigious Hochschule fur Musik in Berlin, 18 being the traditional age of entry. I studied with him for another year before changing to Professor Adolph Steiner, who was a highly acclaimed soloist. He is not widely known in the United States because he mainly concertized in Europe.

TF: When did you come to the United States?

ES: I came to Los Angeles in 1952 with my parents and my sister, Alice, a concert violinist. In 1959, my sister and I were invited by the Dean of the Music Department of the University of Southern California (USC) to join the faculty. At first we only taught there on a part-time basis because we were so busy concertizing and touring. After awhile, we attracted so many students that we accepted positions as full-time professors.

TF: Were you on the faculty with Gregor Piatigorsky and Jascha Heifetz?

ES: Yes. I didn't have much contact with Mr. Heifetz except during examinations, but I met Mr. Piatigorsky more frequently, who was a wonderful colleague. Piatigorsky was a very charismatic artist and personality and was a superb teacher, which is documented by the number of his students who have been successful in the music profession -- Nathaniel Rosen, Lawrence Lesser, Stephen Kates and Jeffrey Solow, to name a few. Mr. Piatigorsky and I shared many ideas on teaching.

(Click here for the complete transcript)

|

|

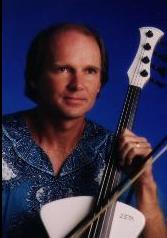

As a mature young man I heard the Casals recordings of the Bach Cello Suites and became absolutely head-over-heels in love with the sound of the cello. Though I greatly admire and love the wonderful repertoire of the cello, my goal was not to become a performing cellist but to use the cello as a voice for my composition and an outlet for my improvisational thoughts. I took the skills and techniques I learned on the other string instruments I play and have incorporated them into my cello style.

I have studied with numerous teachers, but the one who had the most profound effect on me was Martha Gerschefski. For her I prepared my Popper and hacked my way through the gems of the repertoire. I was deathly afraid of performing these gems in our weekly cello class at Georgia State University, so I often bailed myself out by writing and performing my own pieces. The comfort in performing my own works was that no one could tell if I'd interpreted them properly or even if I had made a mistake! After GSU my formal cello training ended and I went on to complete a Doctorate in Composition at the University of Maryland.

My first college teaching job was at Montgomery College in Maryland. My cello skills came in handy; in addition to teaching music theory, I served as principal cellist in their ambitious, sometimes glorious and always friendly orchestra (conducted by cellist Ervin Klinkon). I also taught cello and bass in the college's community school. While at Montgomery College I had the pleasure of writing pieces for the orchestra (in which I often highlighted the cello section). Presently, I am the Coordinator of Theory and Composition Department at Stetson University in DeLand, Florida.

In 1995 I founded the Stetson University Digital Art Ensemble (DAE) in which I play the ZETA MIDI cello. The DAE performs cutting edge new art music, all on MIDI and various electronic instruments. The ZETA cello has added great globs of colors to my cello sound and is really fun to play. At Stetson we are fortunate to have the gifted young cellist David Bjella on faculty. He is a joy to write for. David and I have also performed my cello duet "Fado" (available through Throckmorton's) on numerous occasions and recently he and I, along with two of his top students, premiered my latest cello composition "Bliss" for cello quartet. I have been very fortunate to have made a successful career out of composition and cello, two of my greatest loves.

by Tim Finholt

The first day consisted of two master classes, one with Maria Kliegel and the other with Gary Hoffman, both former students of Janos Starker (see the Master Class Reports). Maria Kliegel's master class was peppered with ironies. Particularly eyebrow-raising was her use of the words "pressure" and "squeeze" in Starker Land; I'm sure there was a slight increase in blood pressure of some in the audience whenever the "p" and "s" words were mentioned. Also entertaining was her telling a cellist with the physique of a professional football player that he needs to work on power in the Prokofiev Sinfonia Concertante. I found her use of the contrasting concepts of masculine and feminine to be particularly insightful with a female cellist whose Haydn was wonderfully delicate and sensitive, though it lacked a certain contrast.

Gary Hoffman's master class was excellent. He brought a perfect balance of humor and willingness to work to the class, as well as a nice balance between technical and musical discussions. I was struck by his frank and understandable admission that Bach is scary to play, even for a musician of his caliber. "The worst thing in Bach is to be afraid of it." He is a wonderfully balanced musician and teacher, having the ability to delve into technical and musical issues in a highly analytical way, as well as in a more spontaneous and creative manner.

(Click here for the complete transcript)

by Tim Finholt

The following are my notes from the master classes in Bloomington, Indiana during the 75th Birthday celebration for Janos Starker (September 12-14, 1999). Please note that, though certain ideas are discussed in terms of specific points in the music, some ideas may be applied in a more general sense.

Bach c minor Prelude

Prokofiev Sinfonia Concertante

(Click here for the complete transcript)

This fantastic site contains articles written by Harry Wimmer for New York's Violoncello Society , detailed technical discussions of different bowing and fingering techniques using specific musical passages, discussions of Leonard Rose and Pablo Casals, a picture gallery, and excerpts from the Anna Magdalena manuscript of the Bach Cello Suites.

**Please notify Tim Finholt at editor@cello.org

of interesting websites that you would like to nominate for this recognition

in the future. Websites will be selected based on their content, cello relevance,

creativity and presentation style!

I just heard Yo-Yo play a recital program in Chicago a few days ago, and I certainly enjoyed the Kodaly very much. It is unlike any other performance that I have heard, but this is not necessarily a bad thing.

I studied the Kodaly with Starker. His vision of it is certainly the most nationalistic one on record. He knows the Hungarian language, and the extent to which that language can (and, in his opinion, SHOULD) influence one's vision of the piece, as well as how to discover the poetry inherent in it.

Starker would not find Yo-Yo's performance to be true to the Hungarian linguistic (and therefore musical) idioms. But I don't think Starker or anyone else would argue Yo-Yo's mastery of the cello, or his committment to his own musical ideas ... and it is this which gave the audience much to enjoy, even if the playing was not typically Hungarian.

Yo-Yo is also a product of the second half of our century, one in which string playing style has gotten more homogenous than ever before. Gone are the refreshingly distinct musical personalities of earlier times (Heifetz, Oistrakh, Kreisler, Milstein, etc.). Even if you preferred one to another, at least you knew who was playing simply by listening to the sound. You didn't have to wait for the radio announcer to say the name. Should it be any big surprise to us that the nationalistic musical distinctions which formerly existed among countries have been blurred as well?

My point is that Starker's Kodaly stands out not so much for being great cello playing (because Yo-Yo and many others can play the notes of the piece), but because he is so at home when the music is of a sort which is at the very core of his being. Most of the Kodaly performances I have heard don't strike me as Hungarian, but I have resigned myself to thinking that this may be an unfortunate side effect of the fact that the world is now more globally-oriented than ever before.

b taylor

>>"Squared" Left Hand or Angled

I'm an adult beginner on the cello. I studied for two months with one teacher and have recently switched to another. Both teachers are professional cellists in world-class orchestras with good reputations as teachers. My current teacher insists that the "square" left hand position with the wrist bent in and the elbow out is the correct position to learn. This contradicts what my first teacher taught me, which was to have the fingers at more of a 45 degree angle to the strings and to "walk" the fingers from note to note. I found this first way very successful and made fast progress in only two months. I find this square position very awkward and difficult and unnatural, but my teacher insists that it's the position of choice and that my other teacher was absolutely wrong in teaching me to "walk" from note to note. How can I find out which is the right way? And how can two professionals have opposite opinions on what should be a very basic skill to teach a beginner?

Barb45

Bob replies: Sounds like you've moved to the wrong teacher. Hard to believe he could play at a high level himself if he truly plays exactly as you describe, unless he has huge hands like Lynn Harrell. But even then, to describe the square hand-set as the position "of choice" amongst cellists of today is ludicrous.

Ryan Selberg replies: My hand, as most cellists hands are, is set more parallel to the ground, closer to a 45 degree angle to the fingerboard, which itself is on a slant of 45 degrees, more or less, to the ground. As to the hand itself, most people's, mine included, don't have the same flexibility when spreading the fingers side to side that they have when lifting the fingers up and down. Just try doing both, holding your hand in front of you, and spreading your fingers side to side. Feel the tension. Now spread your fingers apart up and down, and see how much more natural and tension free it is.

As I love analogies, try this one. If you are walking down a steep incline, (i.e. you are hiking and coming down a steep hillside) you normally would not walk down perpendicular to the hillside, as gravity alone would make that impossible. You flex your legs and step down, extending one leg and bending the other. Often you might even turn more sideways and do it with the same motion. This is more akin to what most cellists hands do. Playing a large instrument is hard enough. Playing without regard to the natural function of the body and hands is begging for trouble. (Just read some of the posts regarding musician's injuries). I would strongly agree with Bob and consider another teacher change. Your current one seems very rigid in his approach and not with the mainstream thought of cello playing. Go to some symphony or chamber music concerts and observe the cellists' hands to see what we are describing.

>>The 'Starker Turn'

At my first lesson of the semester my new cello prof taught me about spinning my left elbow in a little circle to guide the shift of my left hand. I'd been shown this before but never really worked on it. I've only put in 4 hours so far and have seen DRASTICALLY improved results! I hardly have to think about it anymore. My shifting is so much smoother and much more accurate.

Are there any other tricks similar to this pertaining to the right arm (I'm already working on leading with my elbow for martelé-type stuff)? I was amazed how fast results showed up. Usually it takes a day or two, but this was almost instantaneous!

Laura

Susan replies: My current teacher was a graduate assistant with Starker. She talks about putting a circle in the bow arm too, so that your elbow is doing a counter-clockwise circle with every bow. Instead of just upbow and down bow, the entire up and down is one revolution of your right elbow and hand. Also leaning in the direction of the bowstroke helps with fluidity at the tip. It's kinda tricky to explain, and even trickier to do, but it's amazing how much it helps to get a really fluid bow stroke that can be shaped expressively.

Another thing that made a miraculous difference in my left hand was thinking about the flexibility in the first knuckles. It works with the circle in the shift so that your hand can center and balance over whatever finger is being played on, and seems also to make the difference when it comes to sustaining vibrato from finger to finger.

Susan

>>Buying a Cello

What do I look for when buying a cello?

Anonymous

Todd French replies: Let's start with size. Assuming you are a full-grown adult, you will definitely want a full size cello. It's not true that adults starting on smaller sizes (i.e. 3/4) have an easier time. It is just as challenging since the difficulties do not lie with the size of the cello. The simple mechanics are there no matter what size you use.

Also, look for solid woods, all carved. Stay away from plywood and pressed woods (Korean instruments are often pressed into shape). There are plenty of options available for solid, carved cellos in prices from $500 - $2,500,000. Also, you might consider trying both new and older (used, for lack of a better term) cellos. Many companies are making very fine new instruments, and some older German trade cellos are quite fabulous as well. See if you are able to try as many as possible, as the comparison is most rewarding. Also, find a colleague or teacher that can play them for you so you can listen to them.

Do not overlook the bow. Many beginners think of the bow as an "accessory", but that could not be further from the truth. The bow plays such a key role in the sound production and ease of playing that I always recommend that those buying an instrument save a little on the instrument (buy one level down from what they might afford) to spend the extra money on a bow. The first $100 - $200 you upgrade a bow with makes a MUCH bigger difference than if you applied it to an instrument.

>>Thoughts on Popper 7

Popper 7 is a fantastic study if you are interested in Feuermann/Greenhouse/Starker's "walking finger" technique. It is great for learning how to throw down fingers in groups of three or four instead of having to think about each note.

Take the first four notes. If you throw your fourth finger down and then sort of peel the fingers off by pulling back your left elbow you can play these notes in one motion. Then, because you pulled your hand back your fourth finger is "cocked" to be thrown back onto the starting note again by flinging it with the whole arm (like you were going to throw a ball onto the fingerboard!). If you do all these motions fast the first five notes sort of become one circular pattern. You can apply a similar strategy to every 5/6 groups of notes. I found that after learning Popper 7 in this way I could play it at a MUCH faster tempo then if I had tried to play it with a more square hand (my first teacher told me to play with a square hand so the fingers were always right above the notes). I find that this sort of "throwing and peeling" technique which necessitates a highly angled hand has improved almost all aspects of my left hand technique (i.e. I can play faster with more accuracy and more variation in tone colour and vibrato -- mostly due to the fact that this technique becomes literally impossible if you don't relax!).

Charles Brooks

>>Flat Fingers?

What are people's opinion about playing with flat fingers, especially in the higher registers? For me, I've found that I can achieve a much finer tone with flat fingers in thumb position. I also happen to have long fingers that will not stay curved. I have had some teachers complain about this and others say that it is immaterial! Your opinions please!

--Caroline

Paul Tseng replies:

My opinion is that flat fingers are not as bad as some may say. Look at Rostropovich's or even Yo-Yo Ma's. Using flatter fingers has many benefits. Your knuckles are closer to the fingerboard and thus gives you a better center of gravity. The result is that you feel more secure and are less likely to feel as if you might fall off the fingerboard.

If your knuckles stand up in the air then you must actually use pressure and force to hold the strings down, rather than the natural weight of your arm. Pantaleyev (my last teacher) would constantly tap my knuckles reminding me to flatten them out.

Ideally, there should always be a straight line (hardly any breaks or bends) from your elbow to your second knuckle in your finger. Any break in that line interrupts the weight from your arm, which needs to center straight into your fingertip where it holds the string down. This is the same reason you'll see Rostropovich or Yo-Yo's first knuckle (in from the fingertip) straightened out and flat.

An added benefit is that flatter fingers (playing not so much on the tip of your fingers, but on the flat fleshy part) helps with vibrato. For years I could never get the kind of vibrato I desired. I worked very hard and it never came about. But one day I started watching Rostropovich's video tapes and noticed how cool his left hand looked (he and Yo-Yo have really long fingers). So I tried to imitate him simply because his left hand LOOKED cool. Before I knew it, I was getting a richer vibrato than I ever did before by flattening out my fingertips. My own teacher at the time (Stephen Kates) saw what I was doing and asked "Why are you flattening out your fingers? They should be rounded and curved." I said, "That's how Rostropovich does it." He said "Well, that's just him. He's weird that way, only he can do that and still play well." I said "But I sound better this way and I feel more comfortable." Never being one to stick to "rules" he said, "One size does NOT fit all."

Pantaleyev later showed me that what I had learned from watching Slava was correct and showed me how the flat knuckle, straight line position, is to be used throughout the entire fingerboard. One should NEVER have to squeeze the strings down, the weight of the arm should be more than enough to hold them down. With looser fingers one can run around the fingerboard easier and faster, and vibrato will be much more fluid and efficient.

Greg Hamilton replies: I think Paul is right in many respects. If you use the tips of the fingers + thumb as your method to "stop the string," the result will be a grasping, clutching movement which will inhibit the vibrato, facility of fingers, and stamina when playing the instrument, not to mention the physical problems that can occur.

I find that the posture of the left hand fingers that works the best for me is when the first two joints of the fingers (distal and medial phalange) are bent (i.e. supporting the weight of the arm), and then there is a long, mostly straight line from the middle joint to the elbow. This frees up the thumb and prevents the tendency to apply counter-pressure. I've heard some teachers describe this as "hanging on the strings" with the fingers. I have my students do some exercises to help feel this, the simplest being: hold your arm well above the fingerboard, elbow at an 8 o'clock angle and hand relaxed with slightly bent fingers. Move the arm down toward the string as a unit. When you reach the string, KEEP GOING, leaving the fingers to sink into the string while the rest of the arm moves farther down. The result, if done correctly, will show how arm weight factors into left hand technique and demonstrate how the thumb is not needed to help press the strings down.

I encourage my students (90% of which come to me with bad left hand technique) to find the posture that is comfortable for them, using mine as a starting point. Most of them have base knuckles that protrude too high (there is more than one way to make a "C" with your fingers), so I show them how these knuckles should be BELOW the plane of the fingerboard (at least on the A string), not above. This leaves the middle knuckle as the apex of the left hand.

Laura Wichers replies: I'm against the flat finger approach in thumb position. Whoever posted the idea that the arm should be flat from the elbow to the first joint past the base of the fingers has the right idea. If the last joint is also flat, a number of problems can arise, not the least of which can be weird intonation/overall hand position. My current cello prof told me what I'm going to tell you: Hold your left arm/hand/wrist out in front of you (elbow bent). Relax the wrist completely. Then, straighten the wrist until it is flat with the rest of your lower arm. Your fingers naturally curve and your thumb will naturally be about parallel to your wrist, pointing towards the last joint of your second finger. This is how the hand should be in thumb position. In my own experience, playing with curved fingers and a rounded/relaxed hand position greatly increases my 'muscle memory' as to where notes are in relation to each other and when shifting great distances. And contrary to what someone else posted, I think it is easy to be able to concentrate the arm weight into the fingers in the curved position, not having to pinch or press.

The key is to relax your left arm/hand/wrist and make everything feel as natural as possible. If for some reason you find you tense up with flattened fingers, curve them. If the curved position hurts/doesn't work for you (I define this by using the technique for at least a few weeks before deciding you don't like it), then find something that does.

Paul Tseng replies to Laura: As long as your fingers are not unnaturally flattened (to the point where they will contort the rest of your hand/wrist), there is nothing that should hamper your playing.

Many people feel slightly hindered when they begin using this hand position (especially if they are in the habit of having their knuckles pointing high up). The reason they feel constricted is because they are not as free to make very wide ranging motions with their fingers. But my response to students has been, why would you need to move your fingers so high off the finger board, only to have to go so far back down every time you used that finger? How much distance does one really need to put a finger down on a note? It would seem to me that the further from the fingerboard your finger travels the further it needs to travel back. That will take more time. And if you travel back in time it will be more energy; energy wasted. That is why some students get so tired playing Popper 26. Their fingers are using too much excess motion and that tires them out and is inefficient.

I remember watching Sarah Chang play with the Baltimore Symphony. She must have been 14 years old. She's not my favorite violinist but she was quite a player. She moved around all over the stage when she played expressively. But when it came to fast technical passages, suddenly all her motions became very compact and concentrated. This is all for balance and momentum.

Think of a speed skater. Which one would perform better, one who is flailing and waving his limbs about while flying at high speed or one who keeps his arms in close to his body when moving fast?

The bottom line is ... when it comes to fast technical passages, be efficient and relaxed. Don't become tight, but don't expend or waste energy with non-essential motions. I don't mean to say that one should not follow through on large motions. But if you are moving fast you must consider how best to do it.

Think about this: You are given a task to swing a baseball bat to tap a target (about 12 inches from you) 50 times in 1 minute. The only limit you have is time. It doesn't matter what technique you use, what type of stroke you use, you just need to tap it 50 times in 1 minute.

1) How far back will you wind up to swing?

2) Wouldn't it be better to keep the bat really close to the target and use tiny small strokes instead of a whole arm wallop?

Moving your fingers fast is not much different. You need the same factors, speed, accuracy and endurance.

Ryan Selberg replies: I am another of the "flat finger" players. One major point that has not yet been addressed is the actual contact of the finger to the string/fingerboard. The most natural position of the finger is a contact with the pad of the finger, not the end of the finger. Just hold your left hand up in front of you and gently bring the thumb and fingers together. Touch the thumb with each of the fingers, and see where it naturally comes together. I suspect very few will find it natural to touch the ends of the fingers to the thumb. The only time I use that position is to try to pull a sliver out of my finger when I have been doing some woodworking in the garage. When I play in the thumb position, I actually invert the first joint of the fingers (the joint nearest the fingernail) in order to vibrate with the same type of pad contact. However, in rapid passagework, I do raise the fingers to a more arched position.

My teacher studied with Feuermann for awhile, and related Feuermann's analogy about thumb position finger usage. When we walk, we walk heel to toe, or full-footed. But when we run, we use the balls of the feet, not the heel. The same applies to slower, vibrated passages versus rapid passages. I would add a further analogy. Playing on the fingertips for vibrato and shifting would be akin to a ballet dancer walking on point ALL the time. Having the finger on the pad also helps shifting, as you have a bit of resistance to control speed, distance and location. Think of shoveling snow, and the angle of the shovel. Holding it vertical is not the most efficient position for it.

1. Kudos for the Internet Cello Society!

The 1999 Edition of Microsoft's Encarta Encyclopedia recommends the Internet Cello Society when looking for information on the cello. Our site is also going to be featured in StudyWeb, an educational resource site for teachers and students, as one of the best educational resources on the internet (go to their Teaching Resources/Fine Arts/Music section). Our hard work is being noticed!

2. Looking for Fundraiser

The Internet Cello Society is looking for an experienced or professional fundraiser. This person would help with soliciting corporations for donations and perhaps with grant proposals. If you are interested in this position, please e-mail the ICS Director, John Michel.

3. Cello narrowly avoids planter-box fate

Yo-Yo Ma forgot his $2.5 million cello in the trunk of a taxi-cab on October 16. Police recovered it the next day.

4. Tokyo String Quartet cellist change

Cellist Sadao Harada has decided to leave the Tokyo String Quartet. His replacement will be Clive Greensmith, former principal cellist of the London's Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, and more recently professor at the San Francisco Conservatory of Music.

5. 75th Birthday "Cellobration" for Laszlo Varga

Laszlo Varga's 75th Birthday celebration will occur at 3pm on Sunday, November 14, 1999, at Holy Names College, Regent Theater Concert Hall, 3500 Mountain Boulevard in Oakland, California. This event will be in addition to his performance of Strauss' Don Quixote with the Berkeley Symphony, conducted by Maestro Nagano on November 17, 1999. The program on November 14 will consist of congratulatory and salutary remarks, a performance by the Jacques Thibaud String Trio, and a mass cello ensemble performance of selected arrangements by Mr. Varga and Mr. Nagano.

For more information, please e-mail,VCELLO1@aol.com

6. Antonio Janigro Cello Competition

February 17-29, 2000, for cellists under 30. Application deadline is December 1, 1999.

Contact: Antonio Janigro Cello Competition

c/o Zagreb Concert Management

Kneza Mislava 18

Zagreb 10000, Croatia

385-1-4611-797 (phone)

385-1-4611-807 (fax)

7. New San Diego Cello Society Website

The San Diego Cello Society now has a website. Check it out!

8. Kronos Quartet Cellist Change

Cellist Joan Jeanrenaud has resigned from the Kronos Quartet after 20 years with the group. She decided that she no longer wants to deal with the rigorous performance and touring schedule of the quartet, and would like to pursue solo work and collaborations with other artists. Jennifer Culp, who has been guest cellist since January 1999, will take her place.

9. Animated Yo-Yo

Yo-Yo Ma and saxophonist Joshua Redman were recently featured animated characters in a PBS cartoon series called "Arthur." A tuxedo-clad, rabbit-eared Ma appears with his cello. His character also participates in a World Wrestling Federation-style battle between the two musicians to determine which is better, jazz or classical. Go to http://www.pbs.org/arthur for more information.

10. Congratulations, Mr. Leonard

Ron Leonard has retired from his position as principal cellist of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. He is now enjoying his teaching and performing activities at the University of Southern California, and is pursuing solo and chamber music opportunities.

11. Prize Winners

21-year-old Russian cellist Tatjana Vassiljeva, a student of David Geringas, took top honors at the third Adam International Cello Competition in New Zealand. Third place went to another Geringas student, László Fenyö. 17-year-old Gautier Capuçon of France took second prize. A special prize also went to Thomas Carroll of the UK.

12-year-old cellist Kacy Clopton won the junior-high-school division of the 1998-1999 Music Teachers National Association Student Competition. James Hogg, a post-graduate cello student of William Magers at Arizona State University, was a winner in the Collegiate Artist Performance Competition.

12. World Cello Congress Composition Contest

The World Cello Congress III will be awarding a $5,000 prize in its International Composer's Competition. The winning composition will be played by a cello ensemble of more than 200 players on June 3, 2000, at the conclusion of the Congress. Compositions must be received by November 1, 1999. See http://www.towson.edu/~breazeal/cello.htm for more information.

13. World Cello Congress Master Class Contest

The World Cello Congress III is looking for 38 young cellists, ages 12-24, to participate in one of the many master classes that will occur May 28-June 4, 2000. A tape of one movement from either the Dvorak, Haydn D, or Schumann concerti is required as part of the selection process. The deadline for all tapes is December 31, 1999. See http://www.towson.edu/~breazeal/cello.htm for more information.

http://www.inform.umd.edu/rossboroughfestival/rose

** If you know of any other cello events happening around the world,

please send word to Roberta Rominger,roberta@rominger.surfaid.org

**

(Please do not abuse this valuable service; check local libraries and resources before contacting Sarah.)

If you know of newsletters, teaching materials,

references, lists or articles that should be added to ICS Library, please

send data to director@cello.org. (Library

contents will be available to all Internet users; please include author

and written statement of release for unlimited or limited reproduction.)**

http://www.ethanwiner.com/ADULTBEG.HTML

2. Jazz Cello Lessons

http://207.69.201.220/less1bot.htm

3. Article on the Schumann Cello Concerto

http://www.proarte.org/notes/schumann.htm

4. Barrel Cello Picture

http://www.usd.edu/smm/graese5.html

5. Musical Online Magazine

http://musicalonline.com/musicians/cello_bass/cello_bass.htm

6. Jacqueline du Pré website

http://www.geocities.com/Vienna/1844/jdupre.html

7. Video for beginners

http://www.cybersuperstores.com/music/cello.html

8. Cello Methods and Studies

http://www.musicrent.com/celloms.html

9. "Travelcelo"

http://www.streichinstrument.de/traveng1.htm

| Direct correspondence to the appropriate ICS

Staff Webmaster: "webmaster" Director: John Michel Copyright © 1995-1999 Internet Cello Society |

|---|