ICS EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW!!!

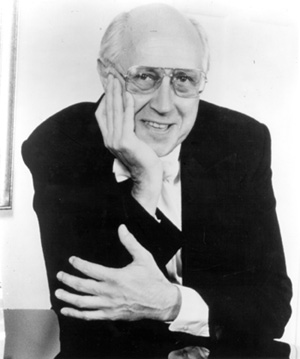

CONVERSATION WITH MSTISLAV ROSTROPOVICH

by Tim Janof

ICS EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW!!! |

|

Rostropovich was born in Baku, Azerbaijan in 1927. At the age of four he started piano lessons with his mother and shortly afterwards began to study the cello with his father. He continued under his father's tuition at the Central Music School in Moscow and then went on to the Moscow Conservatoire, where in addition to his cello and piano studies he began to conduct. He made his public debut as a cellist in 1942 at the age of 15 and was immediately recognized as a potentially great artist. When the war ended his reputation soon spread outside the USSR, principally through his recordings, and when he began touring in the West it was soon apparent that in Rostropovich the world had a natural successor to the great Pablo Casals, who had reigned as the supreme cellist for more than half a century.

Rostropovich has also won outstanding acclaim as a conductor, appearing with most of the world's leading orchestras, as well as conducting and recording many operas, including Queen of Spades, Eugene Onegin, Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk and Tosca. Since 1977 he has been Music Director of the National Symphony Orchestra of Washington. He appears regularly in the UK with the London Symphony Orchestra (he made his UK conducting debut in 1974) and with other leading British orchestras. The London Symphony Orchestra have forged close links with Rostropovich through major festivals which have made an enormous impact on London's musical life. Rostropovich was a close friend of Sergei Prokofiev and was the inspiration behind the LSO's Sergei Prokofiev: The Centenary Festival 1991, featuring orchestral and chamber music, and the world premiere of a cello fugue dedicated to Rostropovich. In 1993 Rostropovich led the Festival of Britten with the LSO, appearing both as conductor and soloist. Other events with the LSO have included Rostropovich's 60th Birthday series in 1987 and Shostakovich: Music from the Flames in 1988. Both on the cello and on the conductor's rostrum, Rostropovich is considered one of the leading interpreters of the music of Shostakovich (with whom he studied composition), Britten, and Prokofiev.

Mstislav Rostropovich is one of the world's most outspoken defenders of human and artistic freedoms. In 1974, after a period of four years during which the writer Solzhenitsyn resided in their home, Rostropovich and Vishnevskaya left the Soviet Union at their own request. Since then he has devoted much time and has given numerous performances to support humanitarian efforts around the world. In 1990, after an absence of 16 years, he made a triumphant return to the Soviet Union with the National Symphony Orchestra of Washington, giving concerts in Washington and Leningrad to enormous acclaim. During the coup of August 1991 the strength of his attachment to his native Russia compelled him to fly, without a visa, to Moscow, to spend those momentous days in the Russian Parliament building and on the streets, where he was hailed as a national hero.

Mstislav Rostropovich holds over 40 honorary degrees and over 30 different nations have bestowed more than 130 major awards and decorations upon him. These include the German Order of Merit, the Gold Medal of the Royal Philharmonic Society, the Lenin Prize, the Annual Award of the League of Human Rights, the ÆPreamium Imperiale from the Japan Arts Association and the Knight Commander of the Most Excellent Order of the British Empire.

TJ: When you burst onto the music scene, people were struck by your white hot performances. Your sound was strong and your vibrato was wide, which was a striking contrast to your predecessors. Where did your unique concept of sound come from?

MR: Let me give you a little background first. My family lived in two-room apartment in Baku until I was seven years old. My mother was a pianist and my father was a cellist who had worked with Casals. There is a picture of me sleeping inside my father's cello case when I was four months old.

My first instrument was the piano, which was my first love. To this day, when I am learning a new cello work, I always start at the piano instead of the cello. One of my father's favorite games was to have me play a melody on the piano starting on a key that he chose at random. I became so proficient at this that at four or five years old he had me do it for friends. My parents never thought that I might have a special talent for the cello.

After my family moved to Moscow, my father played in orchestras that performed in small towns, such as Zaporozh'e. He did this to make some extra money in the summer months. I remember going with my godmother to open air concerts of my father's when I was seven or eight years old. I'd cry when I listened to Tchaikovsky or some other sentimental music, and my godmother would give me a piece of chocolate to soothe me. I soon learned the trick to getting chocolate.

It was around this time that my father said he wanted to teach me how to play the cello. I told him that I didn't want to be a cellist because I wanted to become a conductor instead. He replied, "First you must try the cello. If you are successful with the cello, you can do what you want after that."

My mind, even at that age, was geared towards Romantic symphonic music, not cello music. My interest has always been in the large scale repertoire and that's the sound I've always had in my head, not the cello sound. My "big sound" concept on the cello therefore came from my desire for a more orchestral scale projection. I don't hear a cello sound when I play, I hear an orchestra. I never tried to copy another cellist's sound.

My concept of sound also comes from my experience of playing works with many composers, including Shostakovich, Prokofiev, Britten, Penderecki, and Lutoslawski, to name a few. I also studied orchestration for three years with Shostakovich and I wrote two piano concerti. I am therefore very sensitive to the different orchestrations and timbres of different composers and I learned to vary my sound depending on whose music I was playing. I don't think of myself as having a single sound.

I think some cellists have sounds that are best in certain types of music. My friend Janos Starker's sound is absolutely fantastic for solo pieces like the Kodály Sonata or other more intimate works, but I prefer a different sound when I hear a piece like the Prokofiev Sinfonia Concertante. I believe the Prokofiev needs to have a very strong and full sound.

Were you familiar with the recordings of cellists like Feuermann?

Of course, I was familiar with the playing of many cellists. Feuermann was a phenomenal cellist, but his sound in pieces like the Dvorak Concerto didn't have enough meat for me. Please understand that I greatly respect my colleagues, whether I'm talking about Starker, Feuermann, or others. It's just that I have a different concept of how certain types of music should be played.

Your playing changed significantly over decades. Your playing earlier in your career had a certain simplicity and sense of restraint. It became more rhythmically free and emotionally charged later on. Was there something that happened in your life that caused this change?

I simply evolved over the years. My playing changed as I learned more and as I gained more experience with great musicians around the world. I also started conducting in the 1950's, so my perspective on music-making greatly widened. I became more comfortable with the music making process as a whole and I felt freer to express myself on a more personal level.

I also learned a lot about conducting from people such as Herbert von Karajan. I remember lamenting to him about my difficulties in getting a choir and orchestra to be in synch with each other. No matter what I did, they simply weren't together. He told me to just lower my hands so that the orchestra couldn't see my beat. This forced the orchestra to listen to the choir as they played instead of depending on visual cues. Suddenly the ensemble was perfect!

The Elgar, Walton and Barber concerti were not in your standard repertoire. Why?

I stayed away from the Elgar because I think of that piece as somewhat naïve. The theme from the slow movement sounds like it's about first love, so I think it's more appropriate for a young person. My pupil Jacqueline du Pré played it much better than I because I didn't have the fresh perspective that a piece like that requires. After playing Don Quixote, the Shostakovich concertos, and other works, it was hard for me to go back to a piece like the Elgar.

Why didn't you record the third Britten Suite?

That was a mistake. I have three musical gods -- Shostakovich, Prokofiev, and Britten -- and I feel like I didn't pay sufficient homage to the last one by recording that piece. I was devastated when Britten died so I stayed away from the third suite for awhile, but then I got too busy with other things and I simply never got around to recording it. This is one of my regrets in life.

I remember when Britten asked me to show his War Requiem to Shostakovich. He had composed it in just a couple of weeks. Shostakovich called me two days after I dropped the score off and said that he wanted to hear the work performed, saying, "I'm one hundred percent sure that Britten is one of the greatest geniuses of the twentieth century."

Why didn't you record the Walton Concerto? That seems like a great piece for you.

I didn't have time to play everything. I gave 320 world premieres throughout my career, so I was always extremely busy. I was also busy playing the standard repertoire and conducting orchestras around the world. I could only do so much.

Walton was a great composer and I asked him to write a cello piece for me, but he never got around to it. He did write an orchestra work, Prologo e fantasis, which was his last composition. I asked Barber and Messiaen to write something for me too, but they never got around to it either. Messiaen wrote Concert à Quatre, which is a concerto for flute, oboe, cello, and piano, and he had me in mind when he wrote the cello part. I premiered it after Messiaen died.

Given your phenomenal technique, you must have practiced endlessly when you were young.

I generally practiced at most two hours per day. My record was over a four day period after Shostakovich gave me the score to his first cello concerto. I knew that he was working on it, but I first learned that he had completed it from the local newspaper. I remember wondering anxiously if I would get to see it, since at the time I had no idea if I would be the one to give its premiere. I rushed over immediately when he called and he said that if I liked it he would dedicate it to me. I was in heaven! I went straight home and practiced ten hours that day, ten hours the next day, eight hours the day after that, and then six hours on the fourth day. I only practiced that hard because I was so excited about the piece, and that was the most I practiced in all of my 79 years. I played it for Shostakovich from memory after the fourth day, which was one of the proudest moments in my life.

I was very lucky because I didn't need to practice when I was young. While some performers had to practice every day in order to stay in top form, I didn't. It was as if my fingers had a memory of their own. They never forgot what they were supposed to do.

If you weren't a big practicer then what was that story about you hanging food from the ceiling as you practiced.

That was when I lived in Orenburg, which is in the Urals. I was thirteen years old when my father passed away. He had been the cello professor at the local music academy and I was the best cellist in town after he died, so I was asked to take his place. My family needed the money, so I dropped out of school in eighth grade and took the job. In order to earn some additional cash, I also played some pieces at the local theater as part of an operatic production and I made kerosene lamps to sell at the market. Basically, I was so busy that I didn't have time to practice more than an hour or two per day.

My godmother often baked large flatbread for me, which I tied to a ceiling lamp such that it hung near my head as I practiced. The hard part was catching it so that I could take a bite. The bottom line is that I was so busy that I didn't have time to eat, so I ate while I squeezed in some precious practice time.

What are your priorities when you perform? Are you thinking about the music, the composer, the audience?

I never choose because they are all important, but I do care very deeply about doing justice to the composer. I've had many composers play parts for me on a piano. Sometimes they play very badly, but I see what they feel in their face. I try to re-create their feelings in my performances.

What were Shostakovich and Prokofiev like as people?

Shostakovich was very shy and sensitive and he had a rich inner life that he kept to himself. He avoided confrontation and would fib to spare somebody's feelings. I remember him going up to somebody after a concert and praising their performance and predicting a great future career even though the performance was actually pretty bad. He generally kept his true thoughts and feelings to himself, though he did tend to open up a bit at parties.

Prokofiev, on the other hand, didn't seem to have an unexpressed thought. If he didn't like something, he never considered another person's feelings before he shared his opinion. As an example, Prokofiev once asked Shostakovich why he used so much tremolo in his Fifth Symphony, telling him that it sounded like Aida, which I gather was a bad thing. He could be quite acidic.

Their composition process was also very different. While Prokofiev did a lot of his composing at the piano, Shostakovich worked out a lot of ideas in his head. I do have in my collection small pieces of paper on which Prokofiev would jot down ideas during massage sessions, so he did do some work away from the piano, but Shostakovich's process was much more internal. I took many walks with Shostakovich during which he would suddenly raise his head and become very quiet, which I understood to mean that he was composing.

What did Shostakovich and Prokofiev think of each other's music?

They both had enormous respect for each other, though their tastes were very different. Prokofiev loved Tchaikovsky while Shostakovich preferred Mussorgsky. They listened with great interest to each other's works and got ideas from each other. Shostakovich liked the combination of cello and celeste in Prokofiev's Sinfonia Concertante, so that instrumentation appeared in Shostakovich's next work. Shostakovich also liked the dramatic beat of the timpani after a run of high notes in the cello in the Sinfonia Concertante, so he used that idea in another piece, though he used seven timpani beats instead. Shostakovich thought that the Sinfonia Concertante was Prokofiev's most brilliant work.

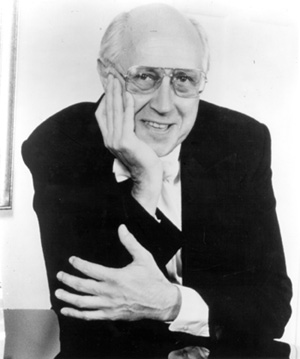

The Soviet composers all kept a close eye on each other. I remember after I performed the Miaskovsky Sonata with Sviatislov Richter, Prokofiev complained that he couldn't hear any of the difficult fast notes in the cello's lower register because the piano was drowning them out. Interestingly, fast low notes in the cello part appeared in beginning of the second movement of Prokofiev's Sinfonia Concertante (see Figure 1), but he made sure that the orchestra isn't playing so that the notes are audible. They all borrowed from each other.

How much of the Sinfonia Concertante was written by you?

Much less than the rumors would suggest. I remember when I played his Opus 58 Concerto in recital with piano. Prokofiev was in the audience and he came up to me afterwards and said, "I think there is some good material in the piece, but I don't like its shape. How would you like to work with me on revising it?" I was so elated by his offer that I practically floated out of the hall!

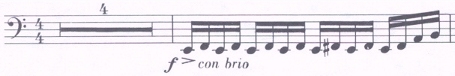

There was only one section where I wrote something, and that was at Number 20 (see Figure 2) in the first movement. Some think I wrote the cadenza, but that was all Prokofiev. He said that he needed eight bars of something virtuosic for the cello. All I had to do was write the cello part since he had already composed the orchestration to go with it. Week after week he'd ask me if I had written something, but I kept putting it off and coming up with excuses. He finally blew up at me and said, "You don't have the talent of Brahms! Brahms wrote tons of piano etudes in addition to his other works and you can't even write eight bars!" That motivated me to finally write it.

I came in the next week with the eight bars and he immediately took it to the piano with a pencil and eraser in hand. As often happened when he concentrated, drool dribbled from his lower lip as he reviewed it. After changing maybe ten notes, he thanked me and said it was good. As I walked down the stairwell from his apartment, he shouted behind me, "Nice eight bars!" It was rare to receive compliments from Prokofiev so that was a great day for me. Unfortunately, he never heard the piece played with orchestra because the Soviet government didn't allow his music to be performed in public. I premiered it in Copenhagen in 1953 after he died.

I also remember when Prokofiev was brought by Miaskovsky to my recital in 1949 to hear the premier of Miaskovsky's cello sonata. Prokofiev said to me, "I shall now start writing a cello sonata for you." I was ecstatic! Being a pianist as well as a cellist, I learned both parts before we met. When we first played it together, I kept correcting him. "I think that F natural should be an F#.... The chord isn't C, E-flat, G, it's C, E natural, G#...." Prokofiev finally said, "Who wrote this, me or you?"

What do you think of the Soviet government's relationship with music and the arts today?

They are so busy with other things that they don't have time to make things worse.

4/5/06

| Direct correspondence to the appropriate ICS

Staff Webmaster: Eric Hoffman Director: John Michel Copyright © 1995- Internet Cello Society |

|---|