by Tim Janof

The Bach Suites have always been a point of contention in the cello world. Unlike violinists and their solo violin works, we do not have a manuscript copy of Bach's cello suites in his own handwriting. The best we have are three manuscripts that may be hand-copied from the original: the Anna Magdalena Bach (Bach's second wife), the J.P. Kellner, and the J.J.H. Westphal manuscripts, the latter two being avid music collectors in Bach's time. Unfortunately, each manuscript contains errors, which provides plenty of fodder for intellectual debate.

My challenge was having to decide which editions to investigate, or more expensively, to buy. Not having a vast financial resource to draw from, I decided to look at the editions that I see most often or ones that seemed intriguing. Inevitably, there will be somebody out there who says something like, "Hey, what about the Bazelaire edition?!" Sorry, when you have over 80 to choose from, you're bound to miss somebody's favorite.

The following are the editions, or more accurately the editors, that I chose to study:

Hugo Becker (1911)

Hugo Becker was a product of the pre-Casals age. During his formative years, it seems that the Bach Suites were regarded primarily as study material for students. In fact, some editions were titled Bach Suites or Etudes[1]. On the rare occasion that a Bach cello work was performed, only a movement or two was ever heard at a time, never an entire suite. As a result of this general attitude, very little was known about Bach, Baroque music, or the performance practice of the times.

Hugo Becker also came from the time of pre-Casals cello technique. I am fortunate to have a recording of Hugo Becker playing. Every time I listen to it, I praise Casals for putting an end to Becker's and his predecessors kind of technique, which employs the "old fashioned" practice of repeatedly sliding between notes (slide up, slide down, slide up, slide down). Casals developed the technique of hopping, stretching, shifting between half-steps, and anything else to avoid the distracting audible shifts. With all this in mind, Hugo Becker's edition gives us a fascinating window into another era of performance practice and technique.

A quick look at his tempi betrays a possible lack of knowledge about the nature of each movement; that each, except the preludes, is based on a dance form. For example, he counts all of the Sarabandes in six beats per measure (ie. eighth notes) instead of three beats per measure, which is now known to be a fundamental characteristic of a Sarabande. Also, some of his tempi are so fast, that they prevent a degree of expression that we, rightly or wrongly, now take for granted; perhaps he too was affected by the general attitude that the Suites were good etude material.

Looking at his fingerings, an old-fashioned approach becomes apparent. He often opts to go up the D string instead of going to the A string in first position, the former a more romantic practice. Sometimes, this is done because he is looking for the more inward timbre of the D string, but other times it seems as if he is avoiding the open A string at all costs. We now know that the open A string, when treated with care, can be a gorgeous sound.

There are many suggested uses of the same finger for adjacent notes, resulting in potentially audible slides. See the typical example from the Menuet I from the first Suite and note the 1-1 and the 4-4 fingerings:

This fingering is considered "old-fashioned." One usually sees 4-1 instead of the 1-1 and 4-1 instead of the 4-4. Today, assuming someone uses Hugo Becker's fingering, he or she is careful to hide the shifts. But, if one listens to Hugo Becker play, he doesn't even try. All shifts are audible. Thank you Pablo Casals!

This edition, though interesting from an historical perspective, does not reflect the advances in cello technique or of later research regarding the Baroque dance forms. It is curious that it is still sold today.

Diran Alexanian (1929)

And then came the great Pablo Casals. What is remarkable about Casals was that, though he still lived in a time when little was yet known about Baroque music or its performance practice, his magnificent musical instincts often led him to play Bach in a manner that has now been proven to be consistent with musicological research. With Pablo Casals, the performance practice of Bach and cello technique would never be the same again.

Diran Alexanian was a protege of Casals and therefore his work reflects the influence of his teacher. Alexanian was obviously a brilliant man. His edition is the great analytical edition, which is still used throughout the world. He analyzed the function of each note and its relationship to its neighbors and to the larger phrase. In order to communicate his ideas, he developed a curious notation that takes getting used to, but ultimately gives one greater insight into the Suites. See a typical example below:

The extension of the sixteenth note bars indicate which group each note belongs to musically.

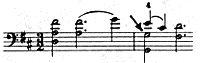

In this edition, we see Casals' influence on cello technique. The frequent use of hops and stretches are employed to avoid audible shifts. See a typical example from the E-flat Prelude:

Notice that it is fingered 1-4-1-4-1, which requires hops and stretches of the hand. This fingering, pioneered by Casals, was considered quite a revolutionary fingering in its day. Compare it with Hugo Becker's fingering:

Though Hugo Becker's fingering is good, Casals' and Alexanian's fingering is better from a musical point of view, though much more difficult. Interestingly, many cellists, such as Janos Starker, use Becker's fingering.

Pierre Fournier (1972)

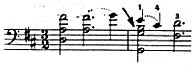

Pierre Fournier seems to have focused his energies into the production of a smooth and beautiful sound (what nerve!). Perhaps, because he was more of a product of the recording age, he chose this approach since it sounds "better" on recordings. To accomplish this, he tended to slur more notes together, resulting in a more even tone. See the following example from the Third Suite Prelude:

Now compare it with the example below from an edition based on the Anna Magdalena Bach manuscript copy of the suites:

Notice Fournier's very generous use of slurs. The advantage of Fournier's slurring is that it is easier to produce a lush and smooth sound. The disadvantage is that the overall energy level of the performance is reduced since fast notes on separate bows sound more lively. It is hard to play with grit and energy if everything is slurred.

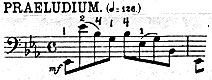

Fournier also has some unusual ideas when playing the suites. For example, look at the fingering from the Prelude of the G Major Suite:

Why does he feel it necessary to alternate a fingered A with an open A string? The open A string is gorgeous here. By changing the timbres in such a short space of time, he creates a disturbance that detracts from the overall line.

One other curious trend that appears in the editions starting with the Casals era and before the "authentic" movement came on strong, is that none of the editions show the 5th Suite played with the Scordatura tuning, ie. with the A string tuned down to a G, as Bach originally wrote it. All the editions only include the 5th suite with the normal cello tuning. Surprisingly, Hugo Becker's edition provides both versions of the 5th Suite, while others, who should know better than Mr. Becker, chose not to play it as originally written. Fournier is among the guilty on this issue. Perhaps this is because, when played with scordatura, one usually plays from music and not from memory, which doesn't look as impressive on stage.

Casals-Foley (1986)

This is a fascinating and yet troubling edition. This edition was not created by Pablo Casals. It was created by Madeline Foley, another Casals disciple, who must have taken copious notes from the Master. Since Casals always left himself room for spontaneity in his playing, the fingerings and bowings in this edition cannot be considered as his, in the strict sense. He often changed fingerings and bowings to suit the moment. Therefore, don't even bother comparing this edition with his recording of the Bach Suites; they are quite different.

Where this edition comes in handy is for musical ideas. The music is heavily edited from a musical standpoint. Crescendos, ritardandos, and other plain English reminders such as "Sing!" or "Move ahead" are prevalent. Also, the "important notes," as Casals called them, are indicated with a tenuto line over them. These are the notes that Casals tended to subtly lengthen to emphasize their importance.

When music is edited as heavily as it is in this edition, it can be dangerous. It is important to remember that these markings are not Bach's; Bach rarely provided any markings except for the very occasional dynamic. Therefore, we must be conscious that when we play from this edition, we will be interpreting an interpretation. And with a strong musical personality like Casals, it is too easy to exaggerate his ideas and sound ridiculous; there are some things that only an artist like Casals could pull off.

Janos Starker (1971)

This is a very cellistic edition. Starker seems to have spent a lot of time solving the cellistic difficulties of the Bach Suites. "I thought of most of the things that troubles all other cellists. And then I solved it in a way."[2] To do this, he developed bowings that are more comfortable and yet still convey his musical ideas. He also, when necessary, changed some notes that were pretty much impossible play well anyway. For instance, see the example below from the Sarabande of the D Major or 6th Suite:

Now compare it with the Anna Magdalena manuscript edition:

Note how the B-natural has been changed to a G, making the passage much less difficult. This naturally raises the question of whether this shows a lack of respect for Bach or just makes him more playable and realistic for struggling cellists. I'll leave that issue to the reader.

The danger of this edition is that, if one does not have another edition that contains the original notes, one could not know that Bach actually wrote something different.

August Wenzinger (1950)

The Wenzinger edition is based on the manuscript by the hand of Mary Magdalena Bach. His edition is the most honest edition since all markings not in the original manuscript are indicated as such: changed slurs are indicated with dashed lines, added dynamics are shown in parentheses, all corrected notes are footnoted. This edition allows the player to start from as close to the Anna Magdalena manuscript as possible. This minimizes the layering of interpretations that occurs with other editions.

Unfortunately, the original Anna Magdalena manuscript is full of errors. Her manuscript contains over 70 errors such as incorrect notes and measures. And her slurs are the most carelessly written of the three known manuscripts.[3] When Wenzinger created this edition, the other two manuscripts were not yet discovered. In spite of this, Wenzinger's still stands tall in the sea of editions.

(4/3/00 Update: Anner Bylsma, in his book, Bach, the Fencing Master, suggests that the slurs in the Magdalena manuscript are actually very readable. He believes that editors have traditionally not agreed with what they see, so they have declared the manuscript as "unreadable" and "full of mistakes," and have changed slurs to be more in line with 19th century ideas on bowing, i.e. bowing sequences identically, starting each measure on a downbow, etc. Anner Bylsma's book calls into question the accuracy of even this fine edition. I recommend that you check out the manuscript for yourself and draw your own conclusions. For an edition where ALL slurs have been deleted so that you can create your own bowings, try the Vandersall edition.)

Dimitry Markevitch (1964)

This is one of the most interesting Bach Suite editions I have seen. Markevitch, a noted cello scholar and author, based his edition on the three available manuscripts: Anna Magdalena, Kellner, and Westphal. It has a very informative preface that discusses the research into the origins of the suites and performance practice issues, and represents some of the latest research into the Bach Suites. His edition is also very clean and free of fingerings, except in the most difficult passages, which is quite refreshing.

Showing his knowledge of the Baroque dance forms, most Sarabandes start with an up-bow so that the second beat gets the required emphasis with the naturally stronger down-bow.

However, he seems to have an unusual propensity for starting upbeats with a downbow, or starting pieces with a bowing opposite to the intuitive bowing. For instance, he starts the D Major Suite with an up-bow:

I must confess that this doesn't make much sense to me and that many of his ideas seem self-consciously eccentric. But I am grateful to him for making me at least stop and think about possibilities that I have never considered.

Conclusion

So, which edition or editions should one buy? If you buy nothing else, you must have the Wenzinger edition since it is the most honest edition I have seen. The Casals-Foley edition is useful for musical ideas. The Starker edition helps solve many technical difficulties of the Suites. And the Markevitch is useful from a scholarly point of view and is mind-expanding.

But we must recognize that no edition, if studied, survives unmarked by the player. The instant we put a mark on the music, we have started the process of creating our own edition. In order to stay as close to Bach as possible, it then makes sense to start with an edition which is as close to the original as possible. If we don't, we will be interpreting an interpretation, which may have already been an interpretation of another interpretation, or previous edition, and so on. Though there are "only" 80 or so published editions, there really is one edition per cellist.

P.S. Number "81" is about to come out: the Neue Bach-Ausgabe edition. A fourth manuscript by an unknown copyist has been recently discovered. I guess, they will never stop.

P.P.S. You can bypass all of this and use the Vandersall edition, a wonderfully clean version in which all articulations (i.e. slurs) have been eliminated, leaving only the notes. It is also devoid of fingerings. Then you can create your own bowings and fingerings from scratch. What a great idea!

| Direct correspondence to the appropriate ICS

Staff Webmaster: "Drcello" Director: John Michel Copyright © 1995- Internet Cello Society |

|---|